Understanding Core Injury, Athletic Pubalgia and Sports Hernia: Essential Insights and Treatments for Core Health

The core is the most crucial area of the body for athletes and non-athletes alike. It serves as the body's engine room, generating and distributing power, speed, and explosiveness. The core is a complex and multifaceted system, acting as the central hub for nearly all human movement and stability. KNOSIS Physical Therapists are experts in diagnosing and treating conditions related to core dysfunction. Issues such as lower back pain, pelvic floor disorders, and “core injuries” often stem from imbalances or weaknesses within the core system.

This article highlights our expertise in treating “core injuries” (formerly known as athletic pubalgia or sports hernia) and our collaboration with some of the world's best surgeons. We have helped amateur and professional hockey, basketball, and soccer players, as well as non-athletes, recover from debilitating pain originating from their core.

Introducing the Core

To truly understand the core, we must recognize its complexity, which includes a broad range of muscles, tendons, and connective tissues working in concert.

Structural Foundation: At its most fundamental level, the core includes the pelvic floor, diaphragm, abdominal muscles, and muscles of the lower back and hips. These structures form a cohesive unit that provides both stability and flexibility. The pelvic floor acts as a supportive sling, the diaphragm regulates intra-abdominal pressure through breathing, and the abdominal muscles (such as the transverse abdominis and obliques) offer critical support and movement capabilities.

Functional Integration: The core’s role extends beyond mere structural support; it is integral to virtually every movement we perform. This system coordinates and transmits forces generated by the upper and lower body, ensuring efficient and effective movement patterns. Key muscles like the rectus abdominis, external obliques, and erector spinae, along with deeper stabilizers like the multifidus and psoas, all contribute to this dynamic interplay.

Core Stability and Movement: Core stability involves maintaining the integrity of the spine and pelvis during movement, which is crucial for preventing injury and optimizing performance. This stability is achieved through a delicate balance of muscle activation and relaxation, allowing for both rigidity and fluidity as needed. For example, during activities like running or lifting, the core must stabilize the torso while allowing for the necessary range of motion in the limbs.

In summary, the core is not just a collection of muscles; it is a dynamic, integrated system essential for maintaining the stability and functionality of the human body. Understanding its complexities allows us to better address and optimize our physical health and performance.

The Anatomy of a “Core Injury”

To understand what a core injury is, we must begin with the anatomy. There are four main components of the pelvic core:

Two ball-and-socket hip joints

Pubis

Backbone

Muscles attaching above and below

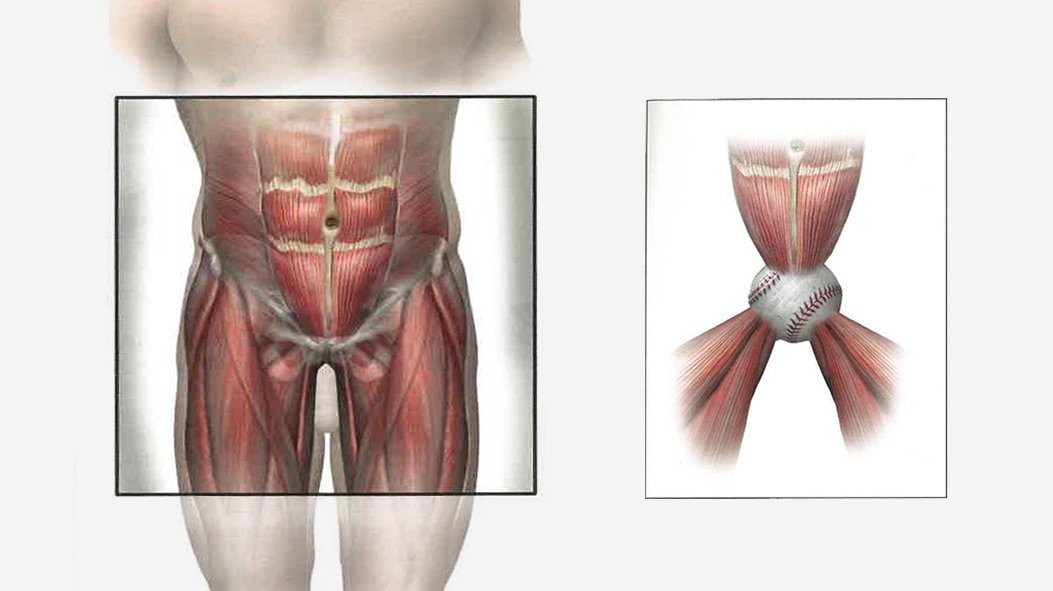

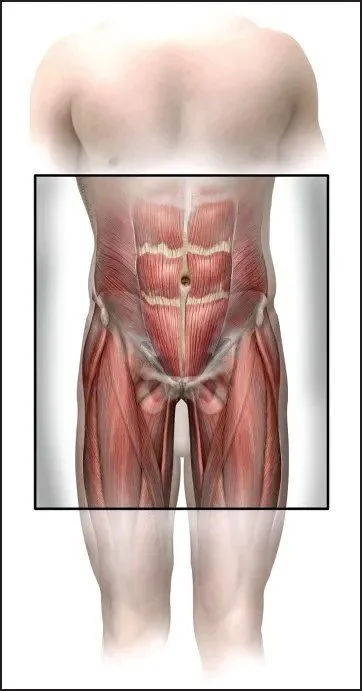

Gordon, Rob. (2019). Fig. 8-10 [Illustration]. Meyers, William C. Introducing the Core: Demystifying the Body of an Athlete. 1st Edition.

In this first figure, you can see the pelvic core as all the skeletal muscles from the mid-chest to the mid-thigh.

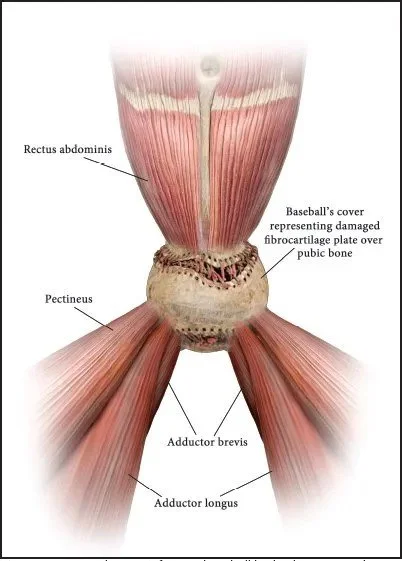

In this second figure, you can appreciate the central muscles that strap to the pubic bone superiorly and inferiorly. We describe this to our clients as the “harness” muscles. The most important harness muscles are the rectus abdominis muscles and three adductors—the pectineus, the adductor longus, and the adductor brevis on each side.

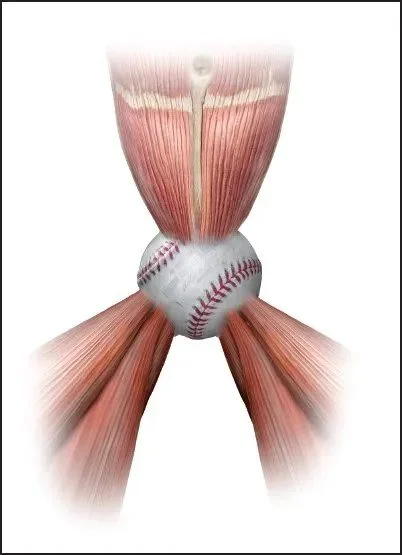

This is one of our favorite images to share with our clients. We ask them to imagine the whole pubic bone like a baseball with a firm, compressible leather cover. Symmetrically, all the core muscles cross by or attach to this baseball. The rectus abdominis attaches from above, and the adductors attach from below – all joining into this hard surface (pubic bone) with a soft cover. The baseball cover represents the fibrocartilage plate that attaches to the pubic bone. If that cover begins to loosen because of asymmetrical pulling from muscles above and below, there is a danger that it will separate from the pubic bone and be pulled off. This loosening leads to inflammation, pain, and a continuum of core injury that includes osteitis pubis.

As described above, the muscles connected to the fibrocartilage plate on the pubic bone are crucial for stabilizing the pelvis and facilitating smooth movement between the torso and legs. This stability acts as a central anchor point, ensuring efficient movement of the entire body. Essentially, these muscles serve as a "harness" that supports the pelvis, ensuring coordinated and effective movements from the legs and torso. When there are imbalances across this harness, core injury can result.

What Is a Core Injury?

A core injury involves tears or micro-tears in the muscles from the chest to mid-thigh, often affecting multiple muscles. These injuries typically occur in muscles connected to the pubic bone, including the abdominal, oblique, and thigh muscles. The rectus abdominis (abs) and the adductor muscles of the inner thigh are frequently involved. Symptoms include sharp or aching pain that intensifies with physical activity, especially during movements involving twisting, turning, or sudden changes in direction.

Understanding Terminology: Groin Injury, Sports Hernia, Athletic Pubalgia, and Core Injury

Hip and groin injuries are categorized into intra-articular (affecting the ball-and-socket joint) and extra-articular (outside the ball-and-socket joint). The first term used to describe these extra-articular injuries was "sports hernia," but this term was misleading. Many cases of sports-related groin pain do not involve a true hernia. The next term that took hold for many years to describe these injuries outside the hip joint to muscles attaching to the pubic bone was "athletic pubalgia." This is a more accurate term; however, the term has evolved to “core injury” or “core muscle injury” for better media compatibility, as "pubalgia" is less suitable for news and television.

Prevalence of Core Injury

It is estimated that 5% to 18% of athletes present to their physician with activity-restricting core injuries. These injuries significantly impact both physical health and athletic performance. Injuries to the upper leg, groin, and hip are among the most common in sports, with recent data showing that "groin problems" are reported by 29% of soccer players on a weekly basis.

Causes and Risk Factors

The most consistently identified risk factor for subsequent injury is a history of previous adductor or groin injury. Core muscle injuries can result from various factors, including overuse, sudden movements, improper form, and direct trauma. Overuse, often seen in athletes who engage in repetitive motions or activities, such as swinging a golf club, can lead to strain and fatigue in the core muscles over time. Sudden movements, like twisting or turning abruptly, can strain or tear the muscles if they are not properly conditioned or warmed up. Core muscle injuries can develop from overstretching the abdominal muscles by extending too far at the waist, overextending the inner thigh muscles during a lunge, or due to poor trunk-pelvic dissociation. It has been our experience that loss of range of motion in one or both hips can be a significant risk factor in developing a core injury.

Recognizing Symptoms

Diagnosing core muscle injuries necessitates skillful differentiation and thorough examination due to the varied sources of pain in the groin and pelvis. Injuries to the rectus abdominis and adductor longus muscles are frequent occurrences due to their opposing force vectors during hip extension and core rotation. Patients commonly report deep, ongoing unilateral or bilateral groin or lower abdominal pain with exercise, exacerbated by change of direction and alleviated by rest, only to return upon resuming sports activities. Other symptoms may include a subjective pulling sensation in the groin or abdominal muscles, chest/rib pain, increased discomfort with exertion, and pain radiating towards the midline of the body and into the adductors.

Diagnosing Core Injuries

Diagnosis relies on physical examination, imaging, and functional testing. X-rays of the pelvis and hips can help identify femoroacetabular impingement and hip dysplasia, aiding in injury prevention during sports activities. A comprehensive MRI with dedicated images of the pubic bone is crucial to avoid incorrect diagnoses. Objective examination assesses tenderness to palpation in the core region, range of motion in the thoracic spine, pelvis, and ribs, as well as diaphragm and pelvic floor control. Strength assessment, especially of adductor-to-abductor ratio, is vital, as a ratio below 80% indicates a 17-times higher risk of injury. Functional and dissociation testing includes single-leg stance, squat, bridge, and trunk endurance tests, along with special tests like the resisted adduction sit-up and cough test.

Treatment Options and Rehabilitation/Recovery

Non-operative treatment involves rest, ice, analgesics, and anti-inflammatories, along with skilled physical therapy immediately after symptom onset. A comprehensive assessment helps identify the cause of joint or muscle irritation, addressing gait and biomechanics, joint and myofascial restrictions, muscle tension, and uncontrolled movements. Techniques like joint mobilization, soft tissue mobilization, manual stretching, and neuromuscular reeducation form the core of treatment. Functional rehabilitation continues with gradual progression to sport-specific activities if substantial improvement is achieved with nonsurgical treatment.

Operative treatment is considered if symptoms persist despite conservative treatment. The goal is to restore normal anatomy across the pubic bone, commonly involving rebalancing the forces exerted by the rectus abdominis and adductors.

KNOSIS in Collaboration with Experts on Core Injury

For the past two decades, our founder Tracey Vincel, myself, and our other PTs have been working alongside pioneer surgeon Dr. William Meyers of Vincera Institute in Philadelphia, his colleague Dr. Alexander Poor, and New York City-based experts Dr. Mark Zoland and Dr Brian Jacob to make accurate diagnoses and important decisions around surgical repair. Given all the body parts that make up the core, from muscles to ligaments to bones, a debilitating core injury can be incredibly difficult to diagnose and treat. Recognizing when it happens can lead to a faster diagnosis and a speedy recovery to get you back in the game. KNOSIS specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of core injuries pre- and post-surgery.

As a testament to their mutual respect and years of collaboration, Dr. Meyers asked Tracey to contribute to his book: "Introducing The Core: Demystifying the Body of an Athlete," which offers an in-depth exploration of the core's vital role in athletic performance and overall physical health. Tracey co-authored Chapter 34, "Don't Forget the Thorax." If you enjoyed this article, "Introducing the Core" is an essential read – especially if you are involved in athletics. This book is an excellent resource for amateur enthusiasts to elite professionals, providing valuable knowledge to optimize core strength, prevent injuries, and enhance overall performance.

Conclusion

Core muscle injuries present unique challenges requiring a comprehensive and individualized approach to diagnosis and treatment. By understanding symptoms, conducting thorough diagnostic evaluations, and implementing evidence-based treatment strategies, physical therapists can effectively manage core muscle injuries and facilitate optimal recovery and function for their patients. If you're experiencing symptoms of a core muscle injury, consult with a qualified physical therapist at KNOSIS for personalized care and support.

References

Core Muscle Injuries in Athletes Alexander E. Poor, MD1; Johannes B. Roedl, MD, PhD2; Adam C. Zoga, MD2; and William C. Meyers, MD1, General Medical Conditions, Volume 17 & Number 2 & February 2018.

Evaluation and treatment of groin pain syndromes in athletes Justin W. Arner1, Ryan Li1, Ashley Disantis1, Brian S. Zuckerbraun2, Craig S. Mauro3. Vol 5 (April 2020).

Comprehensive Approach to Core Training in Sports Physical Therapy: Optimizing Performance and Minimizing Injuries Lewis G Lupowitz, PT, DPT, CSCS, International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy Vol. 18, Issue 4, 2023.

Proposed Algorithm for the Management of Athletes With Athletic Pubalgia (Sports Hernia): A Case Series, Aimie F. Kachingwe, PT, EdD, OCS, FAAOMPT, December 2008, Volume 38, Number 12, Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy.

Introducing The Core: Demystifying the Body of an Athlete.